-

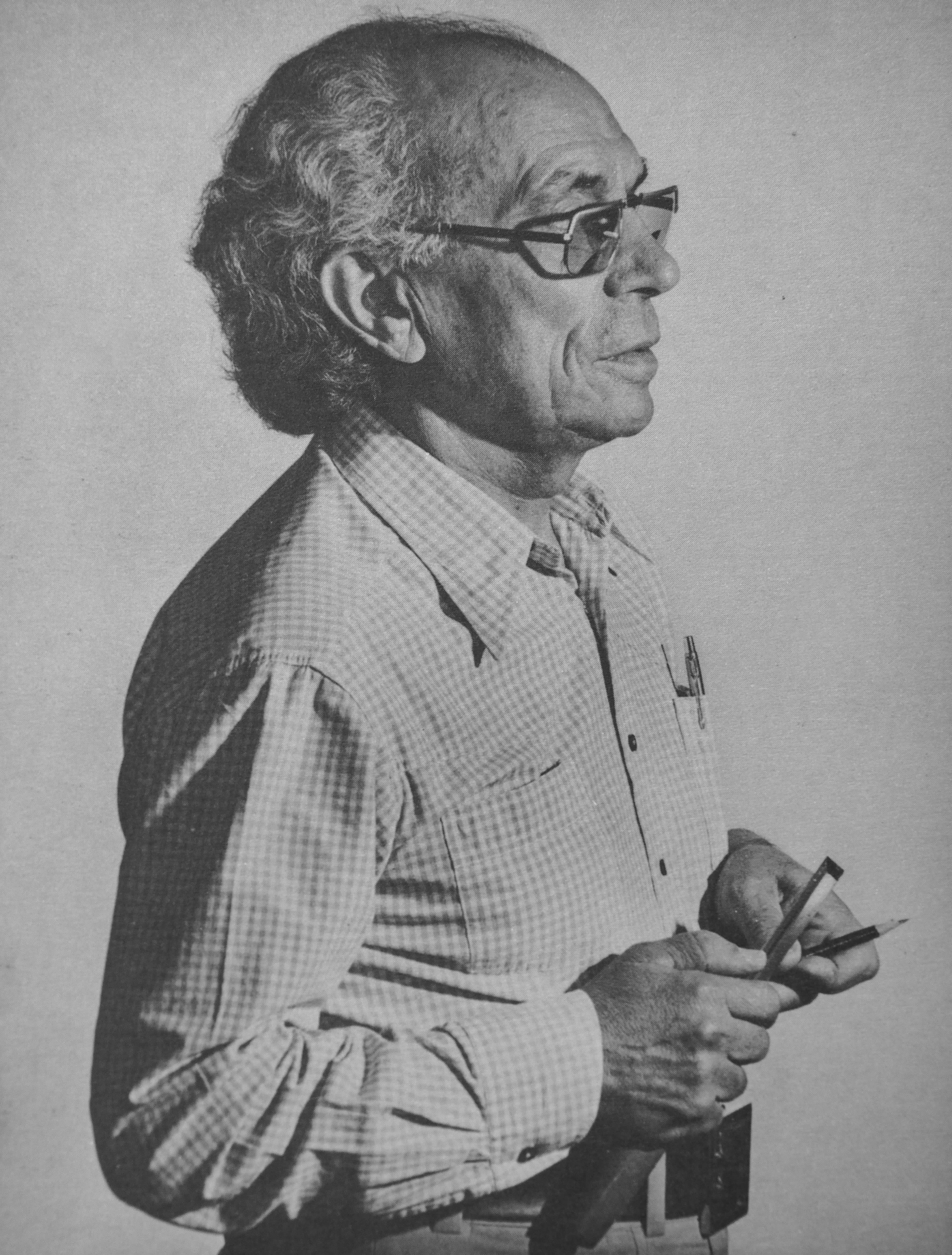

Joaquim Tenreiro

Inventing a modern tropical living -

-

My sensibility comes from the place where I live. It is here that I gain sensibility.

— Joaquim Tenreiro. From an interview in Joaquim Tenreiro: Wood, Art and Design (1985). -

The Life and Work of Joaquim Tenreiro

Mina Warchavchik Hugerth

Joaquim Albuquerque Tenreiro was born in 1906 in the small village of Melo, Portugal, which at the time had 1500 inhabitants. His father and grandfather were woodworkers, and some accounts note that as many as five generations before him worked with wood, undoubtedly informing his future command of the material. By age eight, the young apprentice began training as a craftsman, giving him preliminary insight into designing from a technical and practical standpoint.

During Tenreiro’s childhood and teenage years, the family moved back and forth between Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Portugal, and by 1928, he relocated permanently to Rio. At that time, the city was the country’s capital, with over one million inhabitants and an exciting cultural scene. Tenreiro started working at a small furniture shop while studying drawing and painting at the Liceu Literário Português and later the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios, which led him to join the modernist collective Núcleo Bernardelli. Tenreiro was mostly immersed in a conservative environment and knew how to navigate it, but his yearning to move beyond historicist constraints soon became apparent.

In 1933, Tenreiro started working for the high-end furniture firm Laubisch & Hirth as an assistant to the French designer Maurice Noisière, who had graduated from the École Boulle in Paris. Laubisch & Hirth was one of the biggest firms of its kind in Rio, with 350 craftsmen making custom designs. There, Tenreiro was introduced to various revival styles and contemporary lines akin to Art Deco, familiarized himself with Brazilian woods, and participated in the development of bespoke designs for entire houses. In 1936, he transferred to the furniture and upholstery firm Leandro Martins to work as head of the design department, and between 1941 and 1942, he worked for the furniture firm Francisco Gomes. By 1942, Tenreiro returned to Laubisch & Hirth in the position of his former supervisor and started designing modern pieces, but the company initially declined to put them into production.

At that time, the writer Francisco Inácio Peixoto, who had just had his house designed by the modernist powerhouse-in-the-making Oscar Niemeyer the previous year, went to Laubisch & Hirth looking for furniture for his new home. Niemeyer’s design incorporated elements of traditional colonial architecture with international modernist precepts. Tenreiro was assigned the project somewhat by chance, and the custom pieces he created were more modern and lighter than anything Laubisch & Hirth had previously made (albeit arguably derivative of Scandinavian design), while using traditional materials and manufacturing techniques.

Following that experience, Tenreiro decided to venture out and open his own studio and workshop with José Langenbach, a former salesman from Laubisch & Hirth. Beginning in 1943, Langenbach & Tenreiro offered modern and “English style” (likely Sheraton) designs. As Tenreiro recalled, his partner demanded that traditional furniture be presented, and so they compromised on producing a style that was not overly ornamented.

Tenreiro had become fully immersed in modernist circles by the decade’s end and began furnishing homes designed by Niemeyer, Lúcio Costa, Sérgio Bernardes, Francisco Bolonha, and others. This put him in direct dialogue with these architects and solidified his commitment to creating interiors that responded to contemporary needs while respecting the culture and climate of their making. Langenbach & Tenreiro’s first store opened in 1947, still carrying both traditional and modern furniture, but, as legend goes, within a month, all contemporary pieces were sold and none of the period-style ones did, so from that point onwards, the store only displayed modern furniture.

While the dichotomy between old and new fits well within the modernist narrative, however, there is more to how Tenreiro approached design, even if he didn’t openly address it. In the August 1955 issue of the modern architecture magazine Módulo, Tenreiro published an article about interior design aptly titled “Sobriety, Distinction, and Warmth,” as an opposition to extravagance, affluence, and opulence. In it, he initially discusses how the preceding two centuries had been defined by poor taste, to which modernism provided a break and a solution. He also praises the materials and techniques of Native Brazilians and traditional communities from the Northeast as much as he commends Charles Eames and Isamu Noguchi, but, ultimately, he states that modern Brazilian design and interiors should lie somewhere in the middle and yet be entirely new.

Indeed, Tenreiro’s use of compositional elements like trellises and materials like cane and straw, not to mention wood, clearly reference popular furniture and architecture. His control of form echoes that of his modern counterparts in the United States and Europe. But what is missing from this equation and differentiates Tenreiro from most international players, as well as other designers emerging in Brazil at the time, is precisely his deep understanding of design history, in addition to and beyond both modernist and vernacular practices. Many of Tenreiro’s seats’ backrests allude to the slender spindles of Windsor chairs; he openly discusses his reinterpretations of Dom João V of Portugal–style chairs; some of his commissioned works dialogue with Renaissance pieces, with their intricate wood paneling. Tying all these disparate influences together was Tenreiro’s profound technical knowledge of how materials behaved and how far he could push them.

In 1953, the company opened a shop in São Paulo, and that same year, Tenreiro ended his partnership with Langenbach to found Tenreiro Móveis e Decorações. In the following years, stores in both Rio and São Paulo moved and expanded, but the brick-and-mortar presence was not Tenreiro’s primary source of business; it was a business card. Private commissions to design complete interiors for the cultured elites in Brazil’s larger cities were Tenreiro’s principal occupation.

During the 1950s and ’60s, Tenreiro took on numerous projects to furnish complete interiors. While most of the furniture employed was designed by him and produced in his workshop, documents show that he also selected pieces by Forma (which at the time was the licensed reseller of Knoll designs) and ordered rugs and other soft furnishings from specialized companies. To complete the environments, Tenreiro designed interior architecture elements, including doors, room dividers, ceiling fixtures, and other components that significantly impacted the spaces. As such, Tenreiro moved beyond being a designer of objects to become a designer of interiors. The transition in his practice was such that in 1957, Tenreiro briefly acted as the interior design editor of A Cigarra magazine and soon became a recognizable fixture in the media to discuss interiors and design. At the end of the 1960s, Tenreiro also taught classes on the subject at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro.

Despite his success, Tenreiro’s writings and interviews at that time suggest a growing resentment toward the managerial aspect of his business. He often commented on being exhausted from having to travel and maintain stores in two states, in addition to overseeing the workshop. There is no indication that Tenreiro ever hired assistant designers as his enterprise grew, or that he had an easy time delegating tasks, making for a grueling schedule.

Certainly, fueling the fire of his burnout was a cultural landscape that was drastically different at the end of the 1960s from what it had been in the early 1940s. Over almost three decades, Brazil had industrialized considerably, and several designers and companies expanded the market and desirability for modern design, mainly proposing a much more informal and relaxed sociability, even if under the dark cloud of a military dictatorship. Tenreiro likely felt left out of the field as it professionalized and expanded, and he voiced his discontent several times. When the first industrial design biennial of Rio de Janeiro opened in 1968, Tenreiro expressed his annoyance in the mainstream newspaper Jornal do Brasil for having been left out and for his work having been considered craft, not (industrial) design, even if that was also how he saw his work.

By 1968, Tenreiro decided to leave his company. The official explanation was that he wanted to focus solely on his career as an artist, and indeed, he had wanted to be an artist before he ever became a designer and had never abandoned the practice. Parallel to the furniture and interiors business, Tenreiro had exhibited and won awards for his paintings and sculptures. His art ranged from figurative to abstract, and from painting to sculpture, eventually landing on what he called sculpaintings. In these wooden pieces, Tenreiro returned to his roots, working with his hands once again.

In the following years, he made a few more commissioned designs, but slowly faded from the spotlight, except for a major career retrospective at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in 1978, and another in 1985 at the art gallery of Centro Empresarial Rio, which was accompanied by a publication. In the book, Madeira, Arte, Design, Tenreiro reflects on his life and work and states that his driving force from the inception of his company was to design furniture for his time and in response to the reality of Brazil. That is, his goal was to make Brazilian furniture modern by making it elegant, simple, and respectful of craft traditions. There are complicated contradictions between modernism and the handmade, but Tenreiro doesn’t seem to dwell on that; he believed industrialization was necessary to supply products for the masses, but that it would never produce the finest level of craftsmanship. His take is closer to the sentiment of the nineteenth-century Arts & Crafts than the 1920s avant-garde utopianism.

However conflicted Tenreiro’s place in the design history canon was during his time, today his influence is undeniable. So many who came after him—Branco & Preto, Móveis Artesanal, Sergio Rodrigues, Jorge Zalszupin, Carlos Motta, Claudia Moreira Salles, to name a few—worked by inheriting his sensibilities, proportions, and choice of materials. And while these designers achieved distinctive and remarkable designs in their own right, the genealogy can invariably be traced to Tenreiro and his amalgamation of design history into a cohesive regional output. It seems this understanding didn’t find him in his lifetime. After living his final years in relative obscurity, Tenreiro died in 1992. -

Furniture for my time and in response to the reality of Brazil.

— Joaquim Tenreiro, in interview to Módulo – Revista Brasileira de Arquitetura, no. 87, 1985. -

-

-

-

-

-

Joaquim TenreiroThree-legged chair, 1947

Joaquim TenreiroThree-legged chair, 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (8 chairs), 1947

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (8 chairs), 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroCoffee table, 1955

Joaquim TenreiroCoffee table, 1955 -

Joaquim TenreiroSculpture

Joaquim TenreiroSculpture -

Joaquim TenreiroBar Cart, 1950

Joaquim TenreiroBar Cart, 1950 -

Joaquim TenreiroCredenza, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroCredenza, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroSide Table, 1954

Joaquim TenreiroSide Table, 1954 -

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Sofa, c. 1950

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Sofa, c. 1950 -

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948 -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Coffee Table, c. 1947

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Coffee Table, c. 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroSide Tables (2 units - pair), 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroSide Tables (2 units - pair), 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (6 units), 1947

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (6 units), 1947

-

-

As for the material, I insisted that it be very solid. But visually, the chair was very light. Because the essence of the furniture, you know what it is: it’s perfect joints. The handcraft is the joints. When the joints are perfect, nothing breaks it; it — Joaquim Tenreiro -

-

When I was making furniture, cane weaving had all but disappeared — no one was using it anymore. I brought it back from the colonial tradition. Cane weaving originally came from India and eventually became a Brazilian tradition. For many years, Brazil mad — Joaquim Tenreiro. From an interview in Joaquim Tenreiro: Wood, Art and Design (1985), -

-

-

The Galeries

Spaces of Modern LivingWhen Joaquim Tenreiro opened his first location in 1947, on Rua Barata Ribeiro in Copacabana—a neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro—it immediately stood apart from other furniture retailers of the time. Contemporary newspaper articles often referred to it as Galeria Tenreiro, not as a store, but as a space dedicated to culture and art—one of the few in the city actively presenting modern art. In addition to exhibiting his own work, Tenreiro hosted exhibitions by Bruno Giorgi, Burle Marx, Ivan Serpa, Alfredo Volpi, and others. The showroom functioned not merely as a commercial venue, but as a cultural platform—a role acknowledged in the press of the period. Photographs reveal the evolution of the space. In earlier images, the sign reads Langenbach & Tenreiro Ltda, seen from the inside. In another photograph, taken in 1953, the same address appears from the outside, now under the name Tenreiro Móveis e Decorações—marking the moment when Tenreiro ended his partnership with José Langenbach and established his independent firm. Rather than displaying furniture as disconnected objects, Tenreiro created fully composed domestic environments. Pieces were arranged in carefully staged vignettes that evoked the intimacy and functionality of real homes. These settings did more than showcase design—they proposed a way of living. With clarity of form, balance of proportion, and an intuitive grasp of space, Tenreiro transformed humble materials into refined expressions of Brazilian modernity.

In 1953, Tenreiro opened a second showroom in São Paulo, on Rua Marquês de Itu, near Praça da República, one of the city’s most prestigious addresses at the time. The following year, to accommodate growing demand, he relocated his workshop to a larger facility on Rua 7 de Março, in Bonsucesso, where up to 100 craftsmen were employed. In 1956, the São Paulo showroom moved to Conjunto Nacional, a newly inaugurated modernist landmark designed by David Libeskind, and began operating under the name Tenreiro Móveis e Decorações Ltda. Although the stores in both cities gained visibility and prestige, Tenreiro’s primary focus remained on private commissions. His showrooms were never just retail outlets—they were an extension of his philosophy: spaces where his vision was made tangible, inviting clients to inhabit a new ideal of Brazilian modern living.

-

-

-

When I read a book about the Bauhaus, I felt one of the greatest joys of my life. Walter Gropius explained the teaching method, the development of the student within the school. It was exactly the path I had taken. What a coincidence! I was working in a w — Joaquim Tenreiro. From an interview in Joaquim Tenreiro: Wood, Art and Design (1985). -

-

-

-

-

Joaquim TenreiroManta Solta Armchair (2 units), 1955

Joaquim TenreiroManta Solta Armchair (2 units), 1955 -

Joaquim TenreiroManta Solta Sofa, 1955

Joaquim TenreiroManta Solta Sofa, 1955 -

Joaquim TenreiroDoor, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroDoor, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chairs (6 chairs), 1942

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chairs (6 chairs), 1942 -

Joaquim TenreiroArmchair, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroArmchair, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroDining Table with glass top, 1949

Joaquim TenreiroDining Table with glass top, 1949 -

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chairs with Sticks Backs (8 units), 1948

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chairs with Sticks Backs (8 units), 1948 -

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf , 1950

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf , 1950 -

Joaquim TenreiroRocking Chair, 1947

Joaquim TenreiroRocking Chair, 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948 -

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf, c. 1968

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf, c. 1968 -

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chair (8 chairs), 1950s

Joaquim TenreiroDining Chair (8 chairs), 1950s -

Joaquim TenreiroL-Shaped Armchair (Pair), c. 1958

Joaquim TenreiroL-Shaped Armchair (Pair), c. 1958 -

Joaquim TenreiroCanapé Sofa, c. 1960

Joaquim TenreiroCanapé Sofa, c. 1960 -

Joaquim TenreiroSide Tables (2 units - pair), 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroSide Tables (2 units - pair), 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Table

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Table -

Joaquim TenreiroBloch Desk, 1965

Joaquim TenreiroBloch Desk, 1965 -

Joaquim TenreiroBloch Desk, 1965

Joaquim TenreiroBloch Desk, 1965 -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (6 units), 1947

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Chair (6 units), 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroPartition, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroPartition, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroDaybed / Single Bed, c. 1962

Joaquim TenreiroDaybed / Single Bed, c. 1962 -

Joaquim TenreiroRocking Chair, 1947

Joaquim TenreiroRocking Chair, 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroSculpture

Joaquim TenreiroSculpture -

Joaquim TenreiroDresser, 1950s

Joaquim TenreiroDresser, 1950s -

Joaquim TenreiroSofa, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroSofa, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroRosewood Armchair, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroRosewood Armchair, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroRosewood Armchair (2 units), 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroRosewood Armchair (2 units), 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroSofa, 1950s

Joaquim TenreiroSofa, 1950s -

Joaquim TenreiroLeve Armchairs (2 units - pair), 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroLeve Armchairs (2 units - pair), 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Armchair (2 units), 1948 -

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Sofa, c. 1950

Joaquim TenreiroCurved Sofa, c. 1950 -

Joaquim TenreiroBloch desk , 1965

Joaquim TenreiroBloch desk , 1965 -

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Coffee Table, c. 1947

Joaquim TenreiroEstrutural Coffee Table, c. 1947 -

Joaquim TenreiroBloch desk , 1965

Joaquim TenreiroBloch desk , 1965 -

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroBookshelf, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroCoffee Table, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroCoffee Table, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroEnd Tables (2 units - pair) , 1965

Joaquim TenreiroEnd Tables (2 units - pair) , 1965 -

Joaquim TenreiroChaise, 1960s

Joaquim TenreiroChaise, 1960s -

Joaquim TenreiroFolding Screen, 1950s

Joaquim TenreiroFolding Screen, 1950s -

Laubisch and HirthSide Table (2 units), 1940s

Laubisch and HirthSide Table (2 units), 1940s

-