-

CHAPTER I

WORKSPACES IN HISTORY

-

Office with 15 Comptometers, from the Studios of Felt. Tarrant Mfg. Co., Chicago, 1947

-

This period, which began in the second half of the 19th century and carried on until the end of World War II, is known as the Second Industrial Revolution, and was marked by a series of developments within the chemical, electrical, oil and steel industry, the development of steamships and aircraft, the mass production of consumer goods, the canning of foods and the invention of the electromagnetic telephone. In all areas of society, the focus was on productivity and functionality [2].

In the fields of architecture and design, the valorization of functionality was very present, culminating in the well-known motto “Form follows function” - which came out as a strong trend in Modernism. For Le Corbusier, one of the pioneers of modern architecture, the house should be a “living machine”, with spaces suitable for the functions performed there [3]. From this perspective, when moving the object of analysis from the interior of the house to the interior of the office, we can say that this space could be seen, according to its functionality, as a “working machine”. -

“Taylor was the one who, on behalf of operational efficiency and productivity, developed working methods based on repetitive activities and proposed that the configuration of the work environments should take place with this objective.”

-

Following the functionality principles of work models that aimed at excellence in production and the adequacy of spaces to better meet the functions performed there, modern man found in the office a symbol of success amid the crises of the post-World War II. In Brazil, the development of a national industrial park was driven by the increase in exports to the United States and Europe, which were unable to supply the production for their own product demand [4]. Thus, the production of materials such as plastic, synthetic fiber, aluminum and glass began, encouraging changes in consumption behavior.

In this context, modern furniture achieved a favorable ground for acceptance and dissemination. In magazine advertisements published between 1950 and 1960, we can observe the constitution of these spaces designed to provide the individual, as well as in the industry, with the best conditions to perform their work. In addition to the simplification of structural forms and the relationship between form and function, the design of modern furniture involved large-scale series production and, therefore, making “good” design furniture accessible to the largest number of people. Alongside these assumptions, we also see the themes of Brazilian particularities found in the concern with furniture adaptation to the climate and the land, in the use of native materials and in a focus on the ways of life and traditional production of objects in Brazil [5].

Also as a result of the War, a large number of European immigrants arrived in Brazil during this period, settling mainly in large urban centers, such as São Paulo. Alongside the economic transformations that the country was going through, part of these foreigners fostered important changes in the city through the creation of cultural and industrial local institutions.

NOTES

[1] GOMES, Cristina Caramelo. Análise e Design de Ambientes de Trabalho: Aplicação de conceitos à organização do ambiente de trabalho.

[2] In philosophy, for example, we have Durkheim Functionalism, as a current of thought - which also applies within other fields such as anthropology and psychology. "Its main objective is to explain society, collective and individual actions, based on casualties, that is, functions. In this way, society, or what is observed from this theory, is understood as an organism, composed of organs related and specific functions.”

To know more, see: https://anthropology.ua.edu/anthropological-theories/?culture=Functionalism

[3] BRASILEIRO, Vanessa Borges; SALLES, Cristiane Tomaz de Campos. A casa é uma máquina de morar (?): analisando a casa modernista. Cadernos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Belo Horizonte, v.14 - n.15 - dezembro 2007

[4] WARCHAVCHIK HUGERTH, Mina. Mobilinea design de um estilo de vida (1959-1975). 2015. Dissertation (Masters in Architecture and Urbanism) – Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2015.

[5] SANCHES, Aline Coelho. O Studio de Arte Palma e a fábrica de móveis Pau Brasil: povo, clima, materiais nacionais e o desenho de mobiliário moderno no Brasil. Risco: Revista De Pesquisa Em Arquitetura E Urbanismo. São Carlos, n. 1, p. 22-43, 1 jul. 2003. -

Ariel Brasileiro holds a Bachelor's Degree in Museology from the University of Brasília, Brazil, and develops works emphasizing the formation and management of museums and particular collections, documentation, and material culture. Brasileiro is part of the Bossa team, being responsible for research and documentation activities.

-

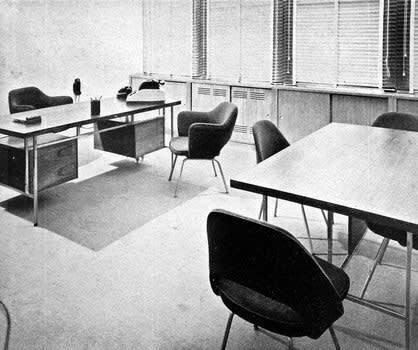

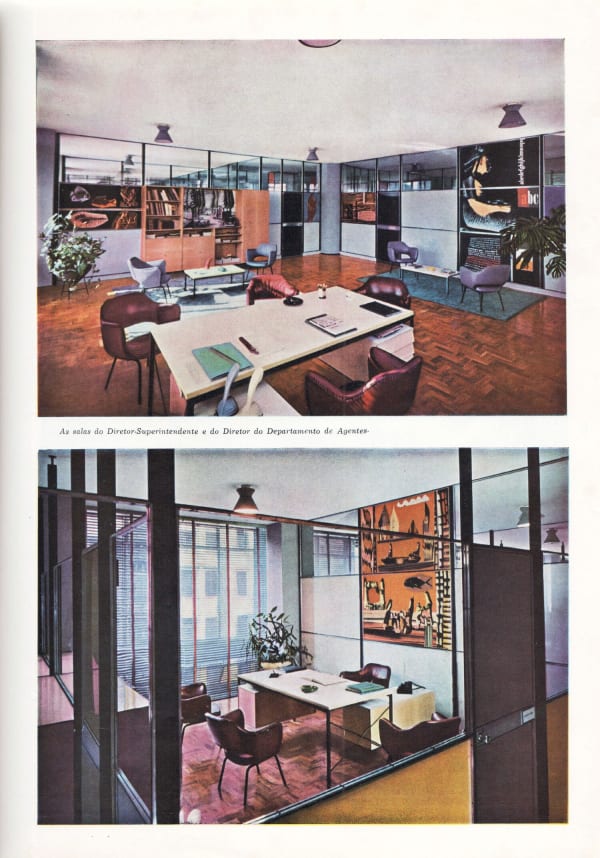

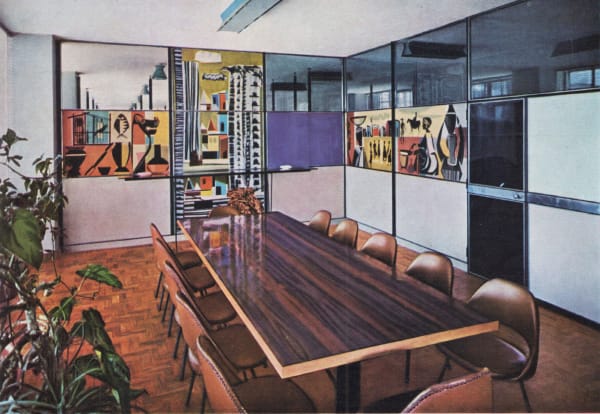

London Bank office in Sao Paulo,Forma Moveis S.A, 1963.

-

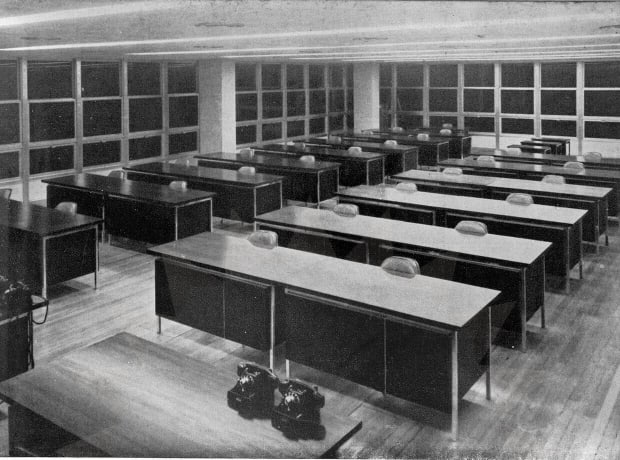

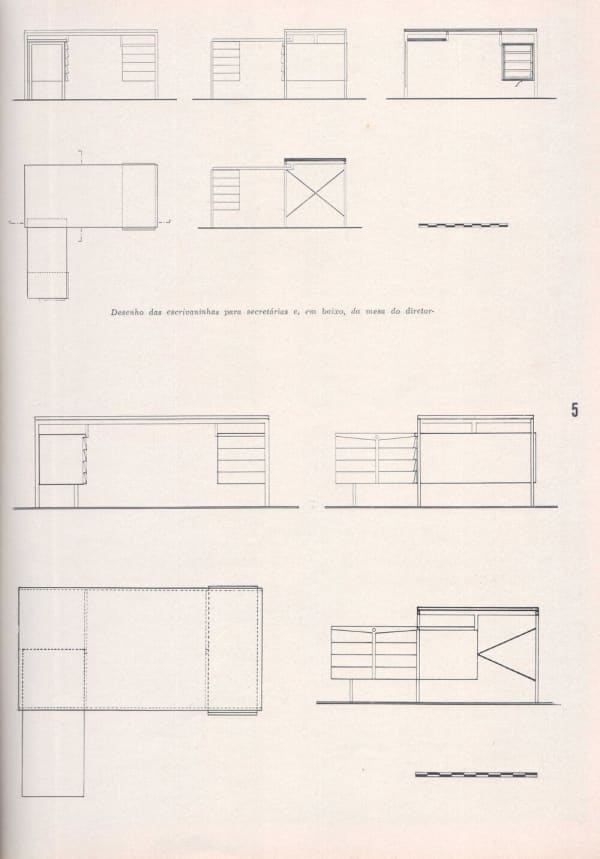

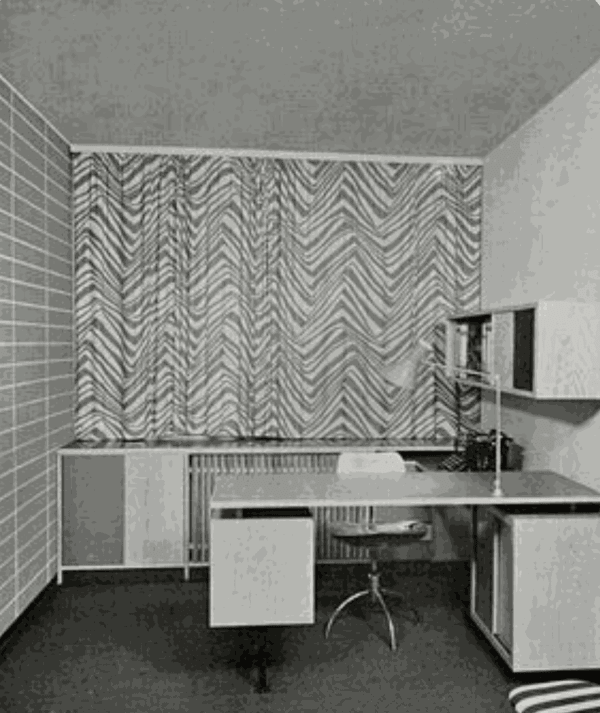

Olivetti Factory in Guarulhos, Sao Paulo,

-

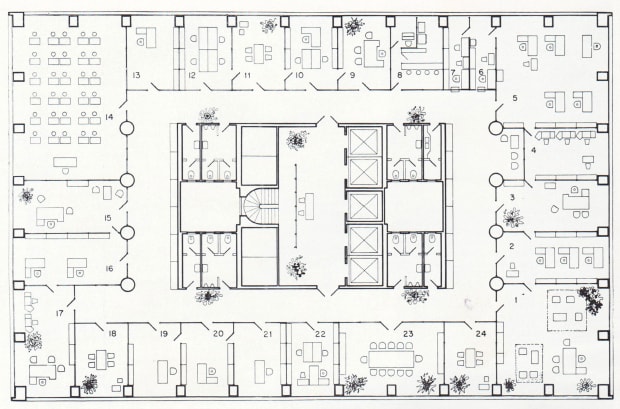

Plan of the Olivetti offices: the director's room occupying ample space and hierarchy defined through the spaces.

-

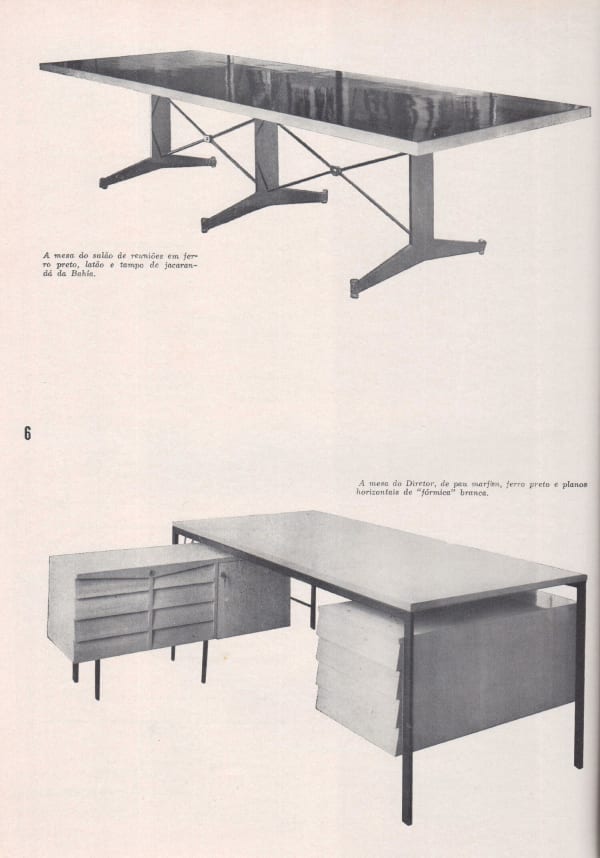

The Olivetti experience presents itself as a great synthesis of an era. The Olivetti experience presents itself as a great synthesis of an era. It allows us to, through modern furniture, understand the economic and social context of industrial expansion in Brazil. It illustrates the philosophical thought currents guided by functionalism and rationalism (expressed in the execution of the interior design for the Palanti project). And finally, it shows the artistic issues in ongoing debate, planned and executed according to national peculiarities, stem from the use of Brazilian materials.

-

NOTES

[1] SANCHES, Aline Coelho. O Studio de Arte Palma e a fábrica de móveis Pau Brasil: povo, clima, materiais nacionais e o desenho de mobiliário moderno no Brasil. Risco: Revista De Pesquisa Em Arquitetura E Urbanismo. São Carlos, n. 1, p. 22-43, 1 jul. 2003.

[2] The idea of the architect's performance from the design of an object to the urban plan was thus implemented, proposed by Gropius at Bauhaus.

[3] Giancarlo Palanti and Lina Bo Bardi, Italian architects that emigrated to Brazil in 1946, got together in 1948 and opened the Studio de Arte Palma and the Pau Brasil Ltda., projects in the Brazilian furniture design sector. With the end of Studio de Arte Palma in 1952, there is a bifurcation regarding the paths of modern furniture in Brazil. Lina, since before coming to Brazil, is dedicated to researching popular culture, Palanti focuses on an industrial design line that culminates in the Olivetti experience.

[4] Le cupole di Zanuso: una fabbrica in Brasile. L'Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, no data. Available in: <https://www.storiaolivetti.it/articolo/81-le-cupole-di-zanuso-una-fabbrica-in-brasile/>. Access in April 8th, 2020. -

Ariel Brasileiro holds a Bachelor's Degree in Museology from the University of Brasília, Brazil, and develops works emphasizing the formation and management of museums and particular collections, documentation, and material culture. Brasileiro is part of the Bossa team, being responsible for research and documentation activities.

-

3. COMPLETE ARTICLE: “INTERIORS ARCHITECTURE FOR OLIVETTI”

P. M. BARDI ─ HABITAT MAGAZINE #49, 1958 -

-

4. INSPIRATION FROM THE PAST

-

IN OUR COLLECTION